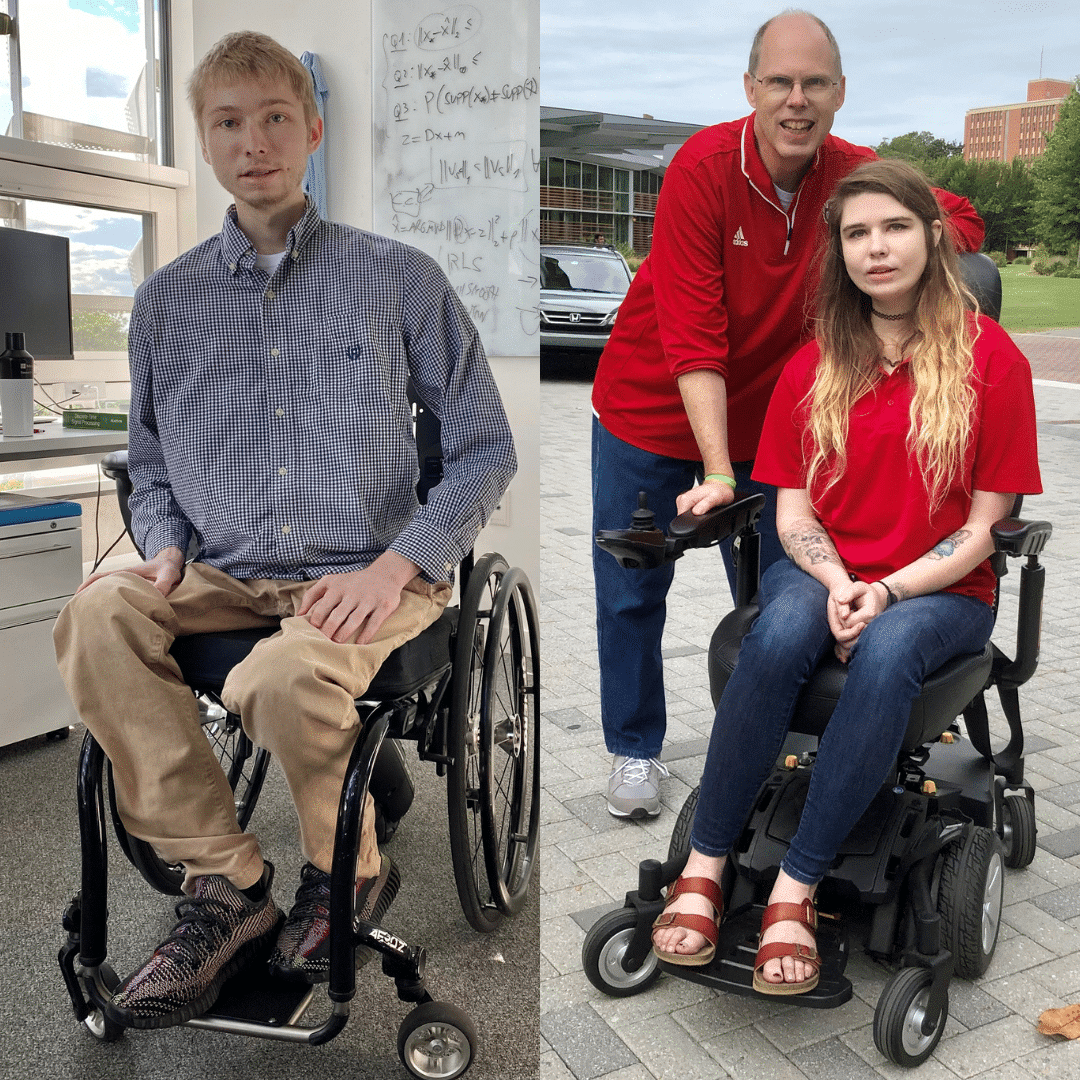

My life was turned upside down when my daughter, Meredith, was diagnosed with Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) in 2003. My son, Jonathan, was subsequently diagnosed with FSHD in 2013.

Since the first diagnosis, I have reached out to multiple caregivers, hospitals, and organizations in an attempt to understand FSHD, as well as to obtain stabilization options and understand the risks and benefits for potential treatments and surgical recommendations which required second, third, and fourth opinions.

The greatest help that my children and I have received has been via their direct caregivers. Some of these world-renowned caregivers (as well as a myriad of rare disease patients, caregivers, and my own children) agreed to help me champion a greater awareness of FSHD (and other rare diseases) through thought leadership pieces culminating with two Springer books: one on muscular dystrophy (Muscular Dystrophy: A Concise Guide; published in 2015) and one on rare disease drug development (Rare Disease Drug Development: Clinical, Scientific, Patient and Caregiver Perspectives; published in 2021).

My personal life ultimately collided with my professional life. I now serve as Vice President of Scientific & Medical Strategy and Head of the Rare Disease Consortium for Syneos Health – a leading provider or contract and commercial research services. Due to my familiarity with visible disabilities, I founded and now serve as Executive Sponsor for the Persons with Disabilities Employee Research Group.

In 2023, I will be working with the Rare Disease Innovations Institute and my daughter, Meredith, among hopefully many other stakeholders, including rare disease patients and caregivers, to discuss the challenges and benefits associated with obtaining access to rare disease therapies.

Every year for Rare Disease Day, I try to pick a different theme and include my daughter, Meredith. Rare Disease Day (RDD) is a chance to honor those living with rare diseases, as well as their families and caregivers, and highlight the obstacles we face as we strive for diversity, equity, and inclusion and a cure for every disease. For the last five years, my daughter provided a keynote address describing what it is like to face the physical and mental challenges of living with a rare and progressive disease. Whether the cause is from the physical disease or dynamics surrounding it, we felt it was time to remove the stigma around talking about mental health, understand the unique challenges of this community, and drive support and solutions to address them.

One thing that those outside of the rare community should know is that we all need hope; the rare disease community especially needs hope and its first cousin, encouragement. We focus on the miraculous progress that some sponsors have made in the rare disease space as success stories to encourage us all, but the overwhelming majority of rare diseases do not yet have a cure or even a disease-modifying treatment. Even a step towards health equity for one group of persons (or rare disease) is a step forward for all groups of persons (or all rare diseases).

I lived in Africa, and I saw firsthand what health non-equity is. Only the rich and educated could afford healthcare. I worked at a clinic which treated children less than five years of age and some of them died due to malnutrition and curable diseases, like malaria. The average age of men and women when they passed was much lower than in the US.

Health equity will be achieved when all persons, including rare disease patients and caregivers – regardless of gender, ethnicity, geography, socioeconomic status, employment status, ambulatory status, mental status, and age, to name a few of the myriad of many other differences – will be able to obtain the same level of care. Health equity will be achieved when there is no social, physical or mental health stigma associated with rare disease.